Faith in Action

Fran O’Brien ’65 was never particularly political. Slight and a little shy, O’Brien wanted to be a teacher, spending her days with children. She wasn’t one to demonstrate on a street corner or shout at a rally.

But in the upheaval of the early 1960s, O’Brien found an unexpected passion — not political so much as religious.

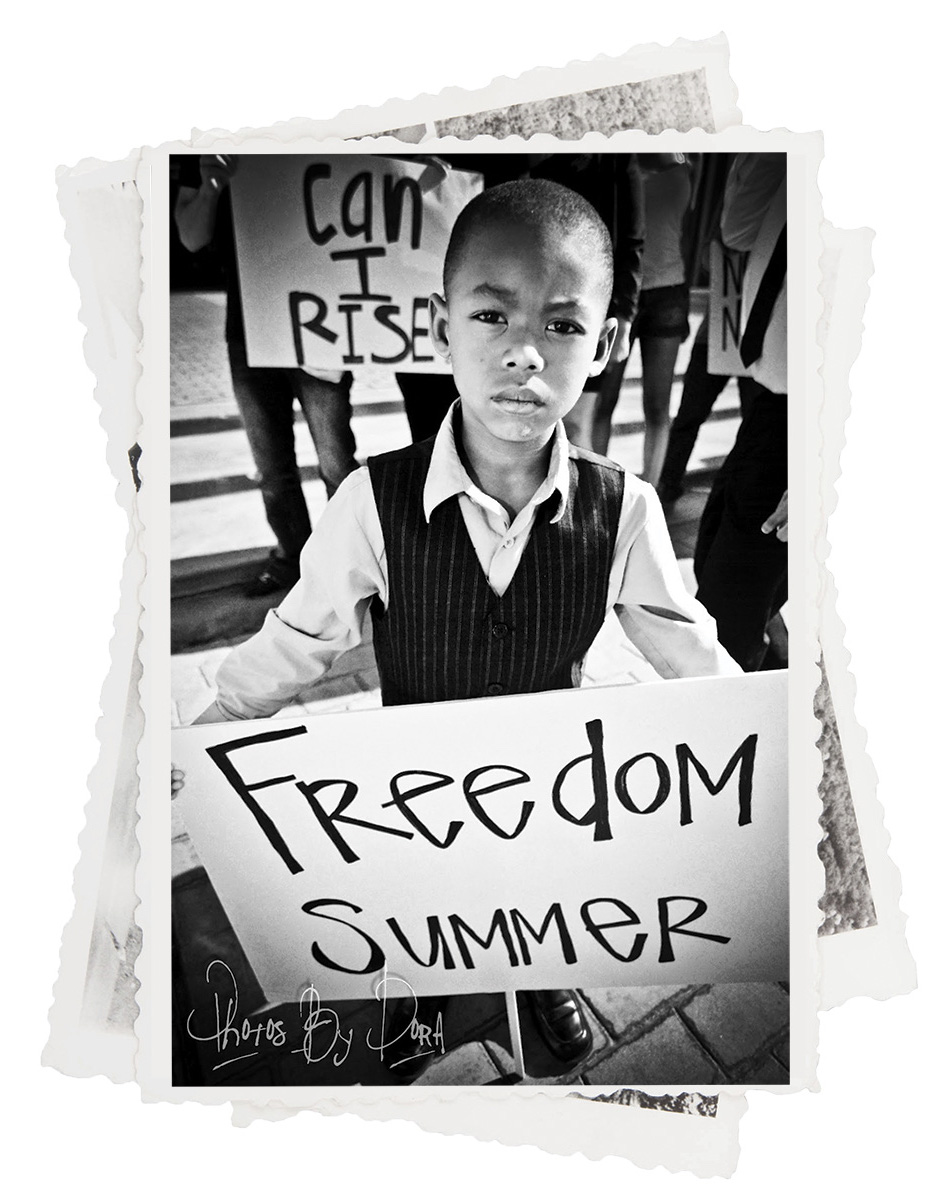

A deeply involved member of Pacific University’s Student Religious Council, O’Brien had a fundamental belief in social justice. It was that belief that led her to become the only Pacific University student to participate in the Freedom Summer of 1964.

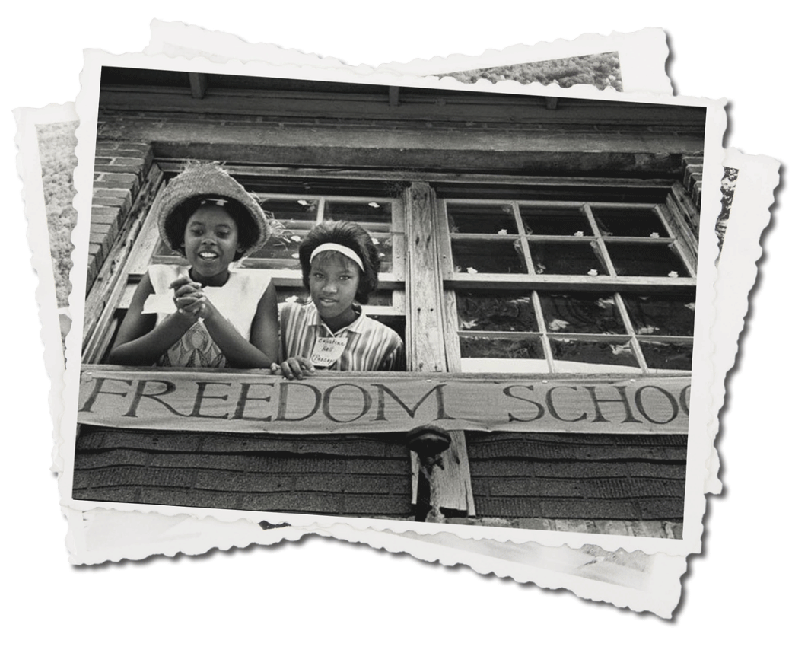

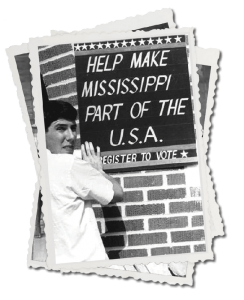

The idea was to send white college students to Mississippi — then the heart of America’s racial inequity — to help black citizens navigate the murky, and often dangerous, process of voter registration, to supplement the education of students whose schools were still separate and far from equal, and to bring white America’s attention to the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement.

It was an idealistic — and controversial — idea, and not one that immediately appealed to O’Brien.

“I thought, ‘It’s a good cause, but not for me.’”

She didn’t have the knowledge to teach Mississippi’s constitution to adults or to give black high-schoolers the physics or algebra lessons they needed, she told herself.

Then, she heard they needed teachers to take care of younger children too, to run recreation programs and art and crafts.

“That was right up my alley,” she said. “I’d been doing that since I was 13.”

"I had in my hand the opportunity to do something." – Fran O'Brien '65

Still, she hesitated — an application completed, but waiting to be submitted.

It was the film Judgment of Nuremburg that changed her mind.

“In one scene, an American judge is talking to a German housekeeper, asking about life under Hitler. She got defensive: ‘We did not know what was happening, and we couldn’t do anything!’

“And I thought, ‘What would I do if someone asked me?’

“It would be one thing if I didn’t know, but I had in my hand the opportunity to do something. If a door is locked and you don’t go through, that’s one thing. But if it’s wide open and someone says, ‘Come in,’ that’s different.

“That took my excuses away.”

It was never supposed to be an easy job.

Volunteers for Freedom Summer were carefully screened to keep out anyone who might not be able to follow the principles of complete nonviolence. And, volunteers were required to come with money for transportation and living costs — plus a fund for bail, if and when they were arrested for their efforts.

The costs became apparent quickly. O’Brien was in the second wave of volunteers to go to Oxford College in Ohio for training before riding buses south to Mississippi.

“We arrived on Sunday afternoon. On Monday, we heard that three of the men who had gone down the week before were missing.

“Bob Moses (director of the Freedom Summer project) waited until one of the men’s wife was out of the room before he told us, ‘They’re dead. They’ve been missing overnight in Mississippi. They’re dead.’

“Six weeks later, he was proved right.”

O’Brien didn’t flinch.

In an essay, Faith and Activism, 40 year later, she wrote:

At no time did I doubt I should have been there. Sometimes I wondered why; often I wondered what I would do and how on earth I could possibly be useful; but never did I use the question word “IF.” It did not occur to me that I might have made a mistake in coming. I KNEW I was meant to be exactly where I was. That is faith. In my case, it led to a unique type of activism.

O’Brien spent the rest of her week-long training gathering ideas for simple art projects for her students and learning how to drop into the fetal position to protect her vital organs if attacked.

She’d need both skills.

O’Brien was assigned to Vicksburg, a relatively safe — by Mississippi standards — community, where she found many people welcoming, if cautious.

“Many of the older black people, they liked what we were doing, but they were stiff, formal. They couldn’t get past the fact we were white. You could almost see the conflict between their head and heart: ‘We agree with what you’re doing, but we can’t have anything to do with you.’”

The retired schoolteacher with whom she lived, Mrs. Garrett, was different.

“She was a remarkable person to make that transition and to teach me.”

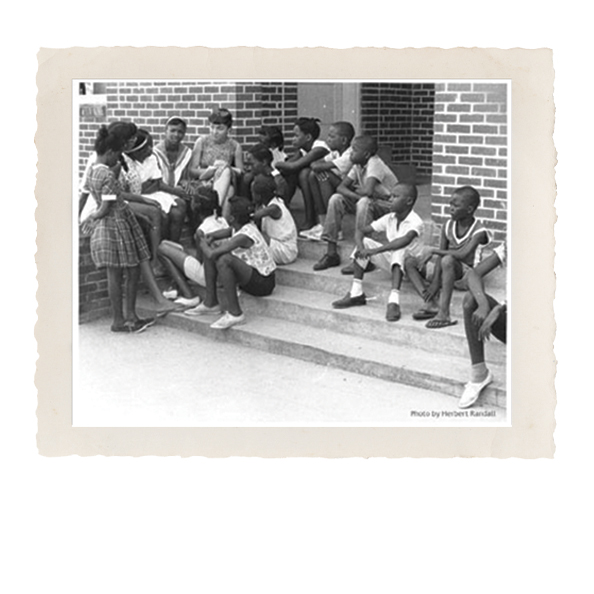

O’Brien taught arts and crafts, led games, played the piano, and started a children’s chorus. But when the children started asking about the American history lessons their older siblings were learning, she paused. There were no children’s history books.

“Mrs. Garrett said, ‘Fran, I didn’t have books. If you know the material, you can teach it.’ The problem was, I didn’t know the material. I was minoring in history at Pacific, but I’d never heard of Fredrick Douglass or Harriet Tubman.

“She said, ‘Well, the kids can’t read the high school books, but I hope you can!’”

And so O’Brien did, helping her young students discover their role in American history, smiling as they added verses to songs like America the Beautiful, and helping inspire them to put on their own American history pageant.

Her work even drew the praise of Martin Luther King Jr., who visited the Vicksburg site in July 1964.

Ever humble, O’Brien doesn’t volunteer this memory — but hers and other stories from the Freedom Summer project are chronicled in the book Freedom Summer by Bruce Watson:

"Many times in the years since Mississippi I have caught myself thinking, "I can't do this!' only to find out that I can."

At first, Fran thought it must be someone who merely looked like (King), but when a friend asked whether she was just going to stand there gawking, Fran jumped in the back. All the way to dinner, other volunteers fell over themselves to tell King about their summer work. Fran sat in silence. Finally, King turned around. “And what about you, young lady?” he asked. “What do you do in the project?”

“Nothing,” Fran managed to say. “I just work with the kids.”

“What do you do with the kids?”

Shyness stifled Fran, but another volunteer burst in and told King what a great teacher she was, doing arts and crafts, backyard games, and now a chorus and piano and sewing lessons. … Fran smiled weakly. King studied her, then asked, ‘Do you call that ‘nothing’?”

“No, sir.”

Then, getting serious as only Martin Luther King could get serious, he said, ‘Young lady, don’t you ever say you ‘just work with the kids.’ Our children are the future and you are forming it.” After dinner, King spoke to a boisterous crowd, but Fran O’Brien would not remember a thing he said that was more important than what he said to her.

If King’s words would leave an indelible mark in her heart in the years to come, another experience would leave a shadowy reminder of the Freedom Summer, one that would trigger nightmares and denial for years to come.

“There was a lot of violence, and I did have one violent incident,” O’Brien says now, almost as an aside. “I was attacked by four members of the KKK.”

It was a rainy night, and she was waiting for a ride at the bottom of a hill in front of the Vicksburg Freedom House. When the car arrived, there wasn’t room for everyone, so she offered to stay behind for the next car.

“(The driver) was black and had grown up in Mississippi. He assumed ‘wait’ meant get the Sam Hill up the hill to the house. I took it literally, though, and just waited there. Sure enough, another car came around, but it was four Klansmen with robes and hoods.”

The men took O’Brien to a vacant lot nearby — or so she believes. At the time, fear distorted her senses. She had no idea where she was or how long she was gone.

“They said, ‘We’re going to make you sorry you came here. We’re going to make you get on your knees and say it.’ They bent me over the hood of the car and beat me with rubber hoses until I fainted.”

When she woke up, she was back at the Freedom House. She thought she’d been gone for hours, but in reality it was only about 30 minutes. She hadn’t even been missed. In shock, she blamed herself, thought herself foolish.

“We’d been told a hundred times, ‘Don’t be alone,’” she said. “At some point, I decided I wasn’t going to tell people.”

She carried the secret for the next 25 years.

“It suddenly seemed like everybody had changed. People who had just seemed to have a different opinion from mine were suddenly horribly racist and bigoted,” she said.

“The most difficult were the people who I thought asked very stupid questions: ‘Can’t it just change gradually?’ I’d forgotten that three months earlier I had thought the same thing.

“Then there were the people who would say, ‘I know there’s a lot of violence, but they’re asking for it.’ That would just set me off, but people didn’t know why.”

Nightmares would follow her for years.

But so, too, would her renewed passion for teaching.

O’Brien had suffered polio when she was 12 and was drawn to teaching children with disabilities after volunteering at a summer camp shortly thereafter.

“I was still using a cane then, and the kids would come to me first, because to them, I was ‘normal,’” she said. “That’s what happens when you segregate.”

After graduating from Pacific, she went on to earn a master’s in special education from San Francisco State University and spent some 36 years teaching.

Her Freedom Summer experiences have been written up in two books and a variety of articles, but it’s likely the three and a half decades working with children that have made the most difference in the world.

“A lot of the issues (in special education) were very similar to the Civil Rights Movement,” she said.

She remembers one young boy who had suffered a hand injury when he was 4.

“His first-grade teacher thought his hand was too unsightly to be in school and had put him in a special education class,” she said. “He had gradually been doing less and less academically, because at the time, special ed had very low expectations.

“Maybe it was my lack of experience at the time, but I thought, ‘If somebody just expects these kids to learn, they will.’ That’s not always the case, but it often is.”

That’s what she had seen in Mississippi.

“The black kids in the south had been told they were not as bright, and many believed it. But as long as the expectations are not unreasonably high, kids will respond.”

O’Brien retired 10 years ago, unable to keep up with the physical demands of working with children with disabilities. But she continues to tutor and teach Sunday school — and neither the lessons of Mississippi or the faith that took her there have faded.

“Many times in the years since Mississippi I have caught myself thinking, ‘I can’t do this!’ only to find out that I can,” O’Brien wrote in 2004. “Not everyone can do the same things — and how boring it would be if we did! But everyone can do something. God planned it that way.”■

This story first appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of Pacific magazine. For more stories, visit pacificu.edu/magazine.