It was spring, 1942 and there was war all over the world.

The Great Depression had ended, but now the Allied nations were fighting for their lives as the second European war of the century metastasized with horrific swiftness into global conflict.

As the world descended into total war, life at Pacific went almost unchanged.

Social activities and classes continued as if everything were normal. The “Men of Mac” serenaded the coeds of Herrick Hall nightly. There were Boxer flashes, chapel programs, a spring picnic and May Day festivities. And, the 32 graduating seniors who had entered back in the fall of 1938 when war was still distant, savored their last months together.

Soon, there would be blackouts, rationing, draft notices, tearful goodbyes, military training, overseas deployment, the shock of combat, telegrams from the War Department…and gold stars on service flags hanging in homes and in Marsh Hall signifying those lost in the conflict. The editor of the Heart of Oak yearbook, Phil Porter (or perhaps his assistant, Bob Beattie, who would die in the war) captured the spirit in a dedication to the Class of 1942:

This Last Rich Year…

A year like this may never come again…nine full, rich months in which Pacific students advanced their dreams of life and drank deeply of the fulfillment of those dreams.There was war in the world beyond, but at Pacific there was dancing, there were concerts, lectures, drama…there was youth and love and hope…

A year like this may never come again…but it is ours…forever.

On America’s entry into the conflict, Pacific’s total enrollment stood at 342. Over the next four years more than 520 students and alumni entered the armed forces and served in every theater of operations. At least 30 men and one woman died while on active duty—most in combat, several in training and two while prisoners of war. Dozens more returned, wounded in body or spirit, to pick up their lives — and their credit hours — where they left off.

Lt. Wayne Hutchens, a popular athlete and charter member of Alpha Psi Omega dramatics honorary, received the Distinguished Flying Cross for safely landing a crippled B-17 bomber in North Africa in April, 1943. He died on a mission to Sicily three months later. Sgt. Brooks Taylor, a Forest Grove High School graduate and star Pacific basketball player, fell to a Japanese sniper in a fierce battle at Sanna Nanda in the New Guinea jungle. Lt. John Furby, a journalism major and promising writer, fought in the defense of the Philippines and was taken prisoner when Bataan fell. He perished in Cabanatuan prison camp.

There was war in the world beyond, but at Pacific there was dancing, there were concerts, lectures, drama…there was youth and love and hope…

Those who died left behind girlfriends, wives, parents, friendships, memories of their time at Pacific and most of all the unfulfilled promise of what might have been. They are, perhaps, Pacific’s most distinguished alumni, for it was they who gave the greatest gift—their lives—to defend freedom in the 20th century’s darkest hour. As time takes its toll, fewer World War II era alumni attend reunion each year. All too soon, no one will be alive who remembers when they left a tranquil, oak-shaded campus to go to war.

Following is the story of one alumnus.

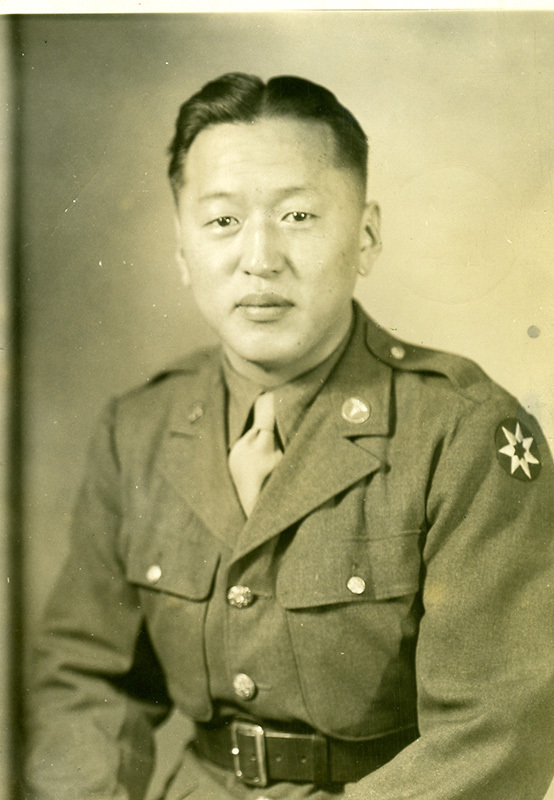

Private First Class Shin Sato: Sacrifice in the Vosges Mountains

Like many young men who left the crowded island nation of Japan early in the 20th century, Yoshinosuke Sato came to the Northwest to find work and perhaps a better life. While putting in long hours in a Seattle sawmill, he found a deal on some land near what is now Beaverton, Ore. and moved there with his wife Asano and young children Lois, Shin and Marie.

Clearing trees and tilling the soil was backbreaking work but the family, like the European immigrants who preceded them, persevered. Gradually the land began to yield bountiful crops of berries and vegetables. Shin Sato grew quickly into a large, good-natured boy who loved sports and had many friends. At Beaverton High School he played football, hung out with his pals, listened to big band music and dated girls. He and older sister Marie often vied for the use of the family’s shiny Chevy coupe.

“We liked and respected Shin,” recalls nurseryman Art Iwasaki, 91, a longtime friend. “He was a big, athletic guy with a sense of humor.”

Sato enrolled at Pacific for the 1938-39 academic year. As a freshman he played football, competed on the newly-constituted boxing squad and participated in fraternity activities as a member of Gamma Sigma. But the next year, as war clouds gathered, he returned to the family farm to help out and earn additional money. When the Japanese Imperial Navy struck Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, life forever changed for Japanese-American families living on the West Coast. Suddenly they were targets of virulent hatred as angry, frightened citizens vented their wrath on perceived enemies.

Then came Executive Order 9077. On Feb. 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, against the advice of FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover and some Army commanders, signed a sweeping directive that gave the Secretary of War unprecedented authority to exclude and remove any group of civilians—citizens or not—from any place he or military commanders chose to designate a “military area” and essentially imprison them without due process for an unlimited term. These areas included all of California and most of Oregon and Washington. While EO 9077 could have been used against any ethnic, racial or political group, it was, in practice, used to target Japanese-Americans.

The Sato family and hundreds of others found themselves at the Pacific International Livestock Exposition (now the Portland Expo Center) housed in cattle stalls, under guard. In July, 1942 they were sent to the relocation camp in Minidoka, Idaho.

As Word War II progressed, the pressing need for military manpower forced the White House and War Department to admit what astute Army commanders had known all along: that Japanese-Americans represented no security threat and in fact were able and willing to fight for their country. So in the spring of 1943, hundreds of second generation Japanese-Americans, known as Nisei, joined what would eventually become the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

After almost a year of intensive combat training in the States, the 442nd was sent to Italy, where General Mark Clark, who had opposed relocation, welcomed them to his 5th Army command. They were put to the test almost immediately, distinguishing themselves in combat at Belvedere. Sato, a machine gunner with E Company, participated in that action.

Then in September the men deployed to southern France, where units of the 7th Army were racing up the Rhone Valley in an attempt to cut off enemy forces before they could retreat into Germany. The offensive stalled at a natural barrier between France and Germany that no army in history had ever penetrated—the rugged Vosges Mountains. Soon, news reached Sato’s battalion that the 141st “Texas” Battalion, which had pushed on ahead, was surrounded and running low on food, water, ammo and hope.

Major General John Dahlquist, with few tactical options remaining, ordered the battle-weary 442nd to rescue the trapped Americans. Sato and his companions, carrying heavy loads, clawed their way up steep, icy hillsides and ravines, taking fire and casualties as they went. Then came a brutal German counterattack. Intense machine gun fire cut down men one after the other. The survivors, seeing their friends fall, suddenly rallied in a desperate charge, running, yelling, firing from their hips. By sheer determination they overwhelmed the enemy positions in close-quarters combat. By afternoon the German guns fell silent; the Nisei solders stood victorious on the rocky knoll.

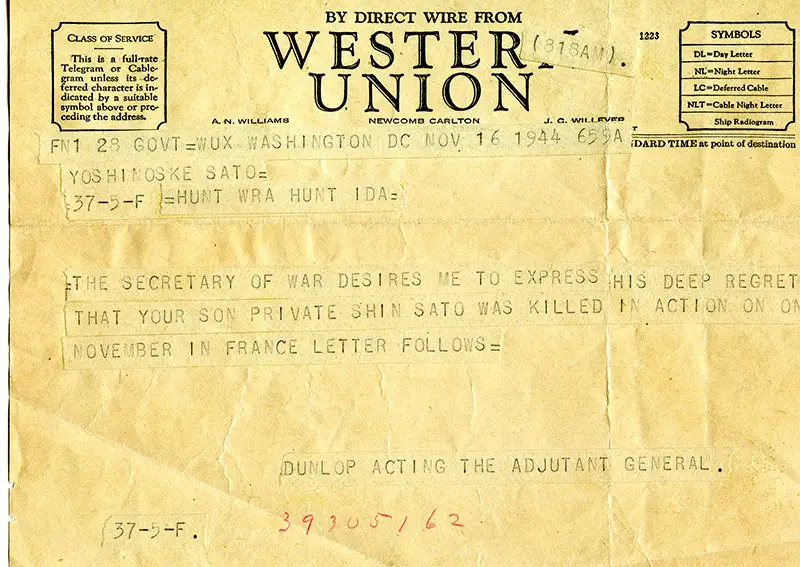

The next morning Sato’s Company E, having secured Hill 617, moved down towards the regiment’s main force to clear and protect its flank. In the early afternoon, as the men advanced, the company suddenly came under heavy German mortar fire. Explosion after explosion ripped through the forest, cutting down men where they stood. Sato fell, mortally wounded, along with several others.

Above on the heights of Hill 645, their Japanese-American companions in 100th Battalion made a final push toward the survivors of the Texas or “Lost Battalion,” as it became known. The trapped GIs saw them approaching cautiously through mist-shrouded trees like ghostly samurai warriors in olive drab. “The chills went up our spines when we saw the Nisei soldiers,” said Lt. Marty Higgins. “Honestly, they looked like giants to us.”

The 442nd had sustained over 800 casualties while rescuing 211 surviving Americans. One of the casualties was Shin Sato, who didn’t live to see the victory he had given his life for. Sato was awarded the Purple Heart, posthumously. In a letter to the Pacific Index published on December 1st, 1944, Sato’s oldest sister Lois, still behind barbed wire at Minidoka, wrote:

“I thought you might like to know that Pvt. Shin Sato, my brother and one of your former students, was killed in action November 1, in Northern France. He was with an American-Japanese unit, the 442nd Infantry. He enjoyed his one year at Pacific a great deal. He was proud to be a member of a fraternity and prized his pin. He was enthusiastic about football and baseball and learned to swim in PE classes. Pacific has good cause to be proud of its students and it gives me pleasure to know that my brother was one of them.”

The wisdom of ordering the 442nd to make costly frontal assaults against fortified enemy positions, even to save fellow American soldiers fighting for their lives, is still questioned by historians. Not open to debate is the Nisei soldiers’ courage. The United States Army ranks the Vosges actions of October 1944 as one of the ten fiercest battles in its history. The 442nd holds the distinction of being the most decorated Army unit in history for its size and length of service.

When the surviving 442nd veterans returned to the States they had to fight another battle—to reestablish their lives. Many families had lost houses, farms and businesses they had worked decades for. While most Americans recognized the Nisei soldiers’ heroism, some openly opposed their return. Sato’s friend Art Iwasaki was denied membership in the Hillsboro chapter of the American Legion. The Berry Grower’s Association passed a resolution barring members from doing business with Japanese-Americans.

Though his family endured tragedy, imprisonment and economic loss, the Satos at least did not suffer the indignity of Kazuo Masuda, a war hero who could not be buried in Westminster, California because the city refused to open the cemetery gates.

On a windy spring day in 1949, the remains of Private First Class Shin Sato, considered Class of 1942, were carefully laid to rest in the Bethany Presbyterian Church cemetery by an honor guard of Sato’s friends and comrades-in-arms. The old graveyard is not far from the family farm in Beaverton where Sato grew up. It is dotted with faded tombstones bearing the names of German and Dutch pioneer families who settled Washington County.

Sato’s gravestone, adjoined by those of his parents and a sister who succeeded him in death, lies in the family plot on the southern slope of the cemetery. The plot is set a bit apart from those of the other families, perhaps symbolically.

The inscription on his stone reads simply:

SHIN SATO OREGON

PVT 442 INF

WORLD WAR II

APRIL 10, 1919 NOV 1, 1944

This story first appeared in the Fall 2010 issue of Pacific magazine.