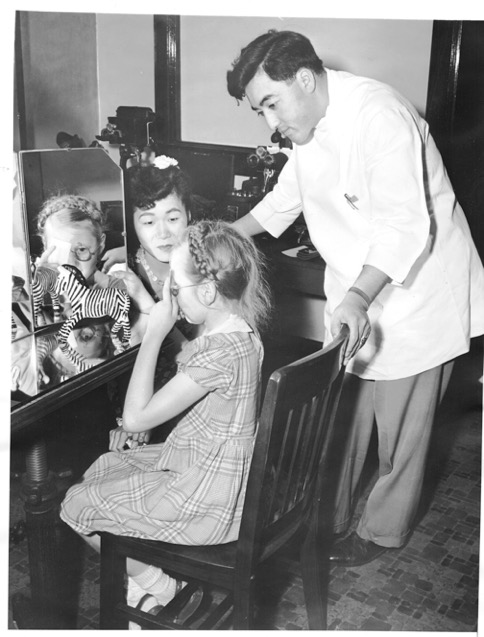

Newton Wesley '39, Hon. '86 never was a student at Pacific University, nor was he a faculty member.

Yet he was one of the most remarkable figures in the history of the university’s College of Optometry. He had a transformational role in its establishment and was a leader in the contact lens field, all at a time when he also was persecuted as a Japanese-American amid and following World War II.

Wesley was born in Westport, Ore., in 1917, as Newton Uyesugi. As a youth, he was a top youth athlete, particularly in basketball. But he suffered from declining eyesight due to a progressive eye disease known as keratoconus, which results in distorted vision.

His family moved to Portland in 1925, and 11 years later, Uyesugi enrolled at the North Pacific College of Optometry. Following his graduation, he opened his practice in Portland in 1939, changing his last name to Wesley, he said, so his patients could find his name in the phone book.

Just a year later, he was offered an unexpected opportunity: His former teacher, Harry Lee Fording, offered to sell North Pacific College to Wesley for $5,000. Then only 22, Wesley joined two classmates, Roy Clunes ’39 and Clarence Carkner ’41, in purchasing the school in 1940. Wesley ’39, Hon. ’86 taught classes there in the mornings and ran his own practice in the afternoons.

The three young men operated the school until the summer of 1942, when they were forced to close. Just after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government began interning people of Japanese descent in isolated camps, particularly along the West Coast.

Wesley, the first licensed Japanese-American optometrist in Oregon, was forced into the Portland Assembly Center in north Portland, on the site of the present-day Expo Center.

With help from advocates with the Japanese American Student Relocation Councils, which helped inmates in American internment camps relocate to colleges in the Midwest and East Coast, Newton and his brother Edward were accepted into Earlham College in Richmond, Ind.

His parents remained in the Minidoka internment camp in Idaho.“There was a time when I could not discuss evacuation — it made me choke up inside of me,” Newton Wesley told an audience in Indiana in 1943, a year later. “Time has been a great healer and I can look at it more objectively.”

Wesley attended Earlham for two years, then transferred to Loyola College in Chicago.Even at a distance, he remained involved in efforts to bring optometry to Pacific. His vision for the school was always to see it gain accreditation from the National Association of Accreditation of Colleges. He also advocated for awarding of a doctorate in optometry, something that was uncommon at the time.

In Oregon, partner Clarence Carkner continued to connect with Pacific, until the university took on the optometry program in Forest Grove. All graduates of North Pacific were granted alumni status by Pacific University.

The Wesley brothers never returned to practice optometry in the Northwest, but Newton Wesley’s influence on the profession continued, driven by his own deteriorating vision.

“Newton had an idea to use contact lenses to treat his keratoconus just as one would use a truss to treat a hernia,” explain historical papers collected at Earlham. “This treatment necessitated extended wear of lenses of the eye and was not possible with technology at the time.”

Few shared his interest in the idea, but it would make him one of the foremost researchers and developers in contact lenses.

Wesley partnered with George Jessen, raising money and building a business called the Plastic Contact Lens Company, later Wesley-Jessen.

The company pioneered gas-permeable lenses that could correct distorted vision and be worn for extended periods. They developed and sold a variety of fitted contact lenses, including bifocals. They also developed a device called the photoelectronic keratoscope, which optometrists used to measure the eye.

Wesley-Jessen was later acquired by CIBA Vision, an industry giant, while Wesley and Jessen went on to create the National Eye Research Foundation (NERF), which worked to create affiliates and partnerships to spread the fitting of contact lenses around the world.

In 1986, Pacific University bestowed upon Wesley an honorary doctor of science degree.

Wesley died in 2011 at age 93. He was widely mourned by professional optometrists, who offered tributes such as the one written by Cary Herzberg, an optometrist who ran NERF for a time. He credited Wesley, among others, for pushing the practice of orthokeratology — using contact lenses to temporarily reshape the cornea of the eye — into the optometric mainstream. The government first opposed the practice, but eventually gave regulatory approval. That initiative, Herzberg wrote in 2011, “brought us into the exciting era we now reside in.”

Herzberg, who had professional disagreements with Wesley, also honored the man’s energy and kindness.

“My best memories of Newton however had to do with his graciousness,” he wrote. “Whether you were invited to one of his many dinners he held or a guest visitor at his foundation he never let you leave without a personal word from himself and a robust handshake. Attending the NERF meetings in Las Vegas every October were lots of fun and learning because Newton would have it no other way."

Earlham College maintains the Uyesugi Japanese American Collection, documenting the experiences of Japanese-Americans who were forcibly interned during World War II. The collection is named for Newton Wesley’s brother, Edward.